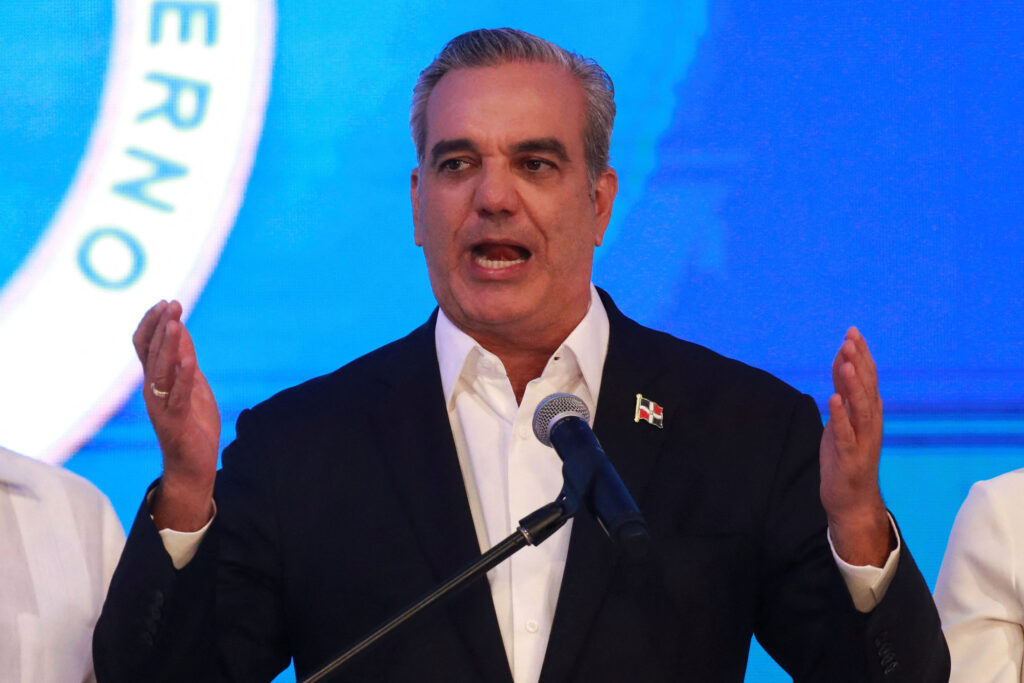

President Luis Abinader of the Dominican Republic is on track for a second term following Sunday’s general elections, claiming victory after his main opponents conceded early in the evening as he maintained a substantial lead in the early vote counts.

The outcome underscores Abinader’s anti-corruption agenda, the government’s stringent measures along its shared border with Haiti, and the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of migrants fleeing the violence-stricken neighboring country. These policies are expected to continue in his next term.

Abinader, one of the most popular leaders in the Americas, garnered nearly 60% of the votes, according to early results. His competitors, former President Leonel Fernández and Mayor Abel Martínez, conceded early in the night.

Supporters at Abinader’s campaign headquarters began celebrating early, with horns blaring and cheers ringing out. In his victory speech, Abinader delivered a nationalistic message, emphasizing change and anti-corruption measures. He notably said little about the government’s strict measures on Haitian migrants and the crisis in their neighboring country.

“The message from the results is clear, the changes we’ve made are going to be irreversible,” Abinader said. “In the Dominican Republic, the best is yet to come.”

While opposition parties reported minor irregularities, the voting process was largely smooth. Many of the 8 million eligible voters were still traumatized by the electoral authority’s suspension of the 2020 municipal elections due to a technical glitch, which seemed to prompt a high voter turnout.

Abinader’s Modern Revolutionary Movement is also expected to secure a majority in the Dominican Republic’s congress, enabling him to push through constitutional changes. This majority would further his anti-corruption and economic agendas, which have earned widespread approval in the Caribbean nation.

Willy Soto, a 21-year-old economics student, was among the supporters. He said Abinader’s anti-corruption measures and economic and educational reforms gave him hope for the future of the country, which has long struggled with political corruption.

“We young people, we see a different kind of government,” Soto said.

A significant part of the president’s popularity stems from his crackdown on Haitian migrants.

The Dominican Republic has historically taken a tough stance on Haitian migrants, but these policies intensified after the 2021 assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse plunged Haiti into chaos. As gangs terrorize Haitians, the Dominican government has constructed a Trump-like border wall along the 250-mile border. Abinader has also repeatedly urged the United Nations to deploy an international force to Haiti, insisting that such action “cannot wait any longer.”

Soto also supported the migrant crackdown, acknowledging the strictness of the policies and the concerns among migrants about Abinader’s re-election. He believed the president’s actions were essential for ensuring the security of Dominicans like himself.

“This isn’t a problem that gets resolved overnight,” Soto said. “The policies he’s implemented, how he’s cracked down, closed the border, and built a wall, I feel it’s a good initiative to control the problem of Haitian migration.”

While popular among Dominicans, these policies have faced sharp criticism from human rights groups, labeling them as racist and a violation of international law. The government has rejected calls to establish refugee camps for those fleeing Haiti’s violence and carried out mass deportations of 175,000 Haitians last year, according to official figures.

“These collective expulsions are a clear violation of the Dominican Republic’s international obligations and put the lives and rights of these people at risk. Forced returns to Haiti must end,” wrote Ana Piquer, Americas director at Amnesty International, in an April report.

As Abinader enters his second term, he has promised to complete the wall dividing the two countries and is likely to continue deporting people back to Haiti amid escalating violence.

The prospect of continued crackdowns has instilled fear in many Haitians, both recent refugees and long-time residents of the Dominican Republic.

Dominicans like Juan Rene have also felt the repercussions. Rene and his cousin were seen pleading at the gates of a detention center on the outskirts of the capital last week, seeking help for his partner, Deborah Dimanche.

Dimanche, a Haitian who has lived in the Dominican Republic for two years, was detained by immigration officers on her way to work. She was taken to the detention center and has been unable to communicate with her loved ones as she faces deportation.

Rene, growing increasingly desperate, spoke with a sense of helplessness.

“They said they won’t hand her over, that they’re going to get rid of her and send her to Haiti,” Rene said. “There’s no one to even talk to.”